While I’ve long known of the 1987 Brundtland definition of sustainability: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” I have always focused on those words ‘future generations’.

Sustainability has always been about the future, future proofing the world in a sense.

I’ve seen sustainability take on a tech-substitution approach. It seems the easiest thing to grasp onto in a consumptive economic system. And, indeed, in the rush of life, substitution is a very easy quick-fix to slip into.

Substitution tells us that we can achieve sustainability so long as we continue consuming. Ensuring that what we consume is (somehow) better than the other thing we could have consumed.

It’s an easy side-step, but it puts us all in a bit of a bind, and it makes us all a bit blind as we simply continue living our lives and going about business as usual, trusting that technology gods or people smarter than us will come up with the inventions we need to escape what seems a hopeless case.

This has actually become, not a circular economy, but a circular problem. An ouroboros. To some an ouroboros represents eternal life, but as the wonderful Tyson Yunkaporta tells us: how can it be a symbol of eternal life if it will eventually eat itself? If anything that is self-destructive, no matter what we call it.

The moment I realised that we need to focus on that word “need” within the Brundtland definition came about through a little desktop research into Manfred Max-Neef.

Manfred Max-Neef developed a matrix of existential and axiological Human Needs which form the foundation of Human Scale Development.

From wikipedia: Human Scale Development is basically community development and is “focused and based on the satisfaction of fundamental human needs, on the generation of growing levels of self-reliance, and on the construction of organic articulations of people with nature and technology, of global processes with local activity, of the personal with the social, of planning with autonomy and of civil society with the state. Human needs, self-reliance, and organic articulations are the pillars which support Human Scale Development.”

The pillars! Of course. My worlds collided. It’s in needs that all my interest areas come together: Wellbeing economics, degrowth, sustainable development, community development, urban environment, the natural world, personal development.

And it was Max-Neef’s articulation of “need” that the 1987 Brundtland definition was based on. I had never considered that those words were obviously carefully chosen and not only that, but a definition of “need” was supplied.

So the Brundtland definition doesn’t just call on us to preserve our way of life for future generations to be able to enjoy the same way of life. It is actually calling us to examine how we expect to live and ask ourselves: Is this actually what I need – or is it just what I want? Sometimes what we want directs us to what is actually an essential need, and we can be alert to this and take ourselves, and our apparent needs a little less seriously in order to get to the real stuff below the surface.

E.g.1. I want to eat chips. Once I start I can’t stop. This is because my body actually needs good fats to function well. There are fats in chips – the body recognises this – but they are not the good kind and so the body desperately triggers the “more” button, in the hopes that its need for good fats will be met.

E.g.2. Social media has captivated us and plays on our dopamine response, a quick buzz when we get a like or a comment on our posts. But we all know we can doom-scroll ourselves to depression or breakdown. We want to doom-scroll, but what this dopamine fuelled bid for connection is showing us is that we actually need real, true, deep connection with people and the oxytocin release this provides. Those relationships are, in fact, something our communities, institutions and cultures were traditionally built around – that is real wisdom-thinking!

There are some sustainability people who are shining a light on appropriate needs.

Initially the Club of Rome’s 1972 publication, The Limits to Growth, called us out to say: Hey, you can’t just keep getting what you want. There are limits to what the earth can sustain! The conversation dwindled around population and resource availability for some time.

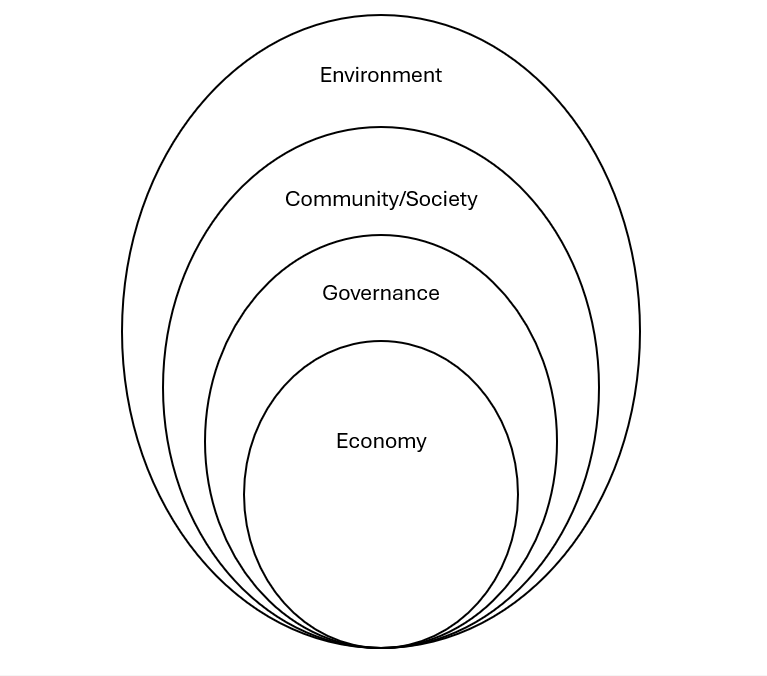

More recently, the Doughnut Economics model seeks to place our needs in the context of sustainability. Looking at a “sweet spot” of human wellbeing where needs are met (not necessarily wants, remember), but the planet is also cared for. However, it doesn’t fully articulate where we ought to be examining our societal expectations for what a good life means. I do think this could be clearer. Sometimes we humans need things spelled out (in the right way, firmly and clearly, with understanding).

However, I think it shows us the balance it takes to live and run the world in a way that is long-term sustainable. The delicate balance which humans (and nature)are designed to exist in is the most difficult thing to obtain. Good systems and our governance should maintain this balance, and not fall prey to the simplicity of more (GDP). That is a clear message of the model.

Another economic movement, Degrowth (possibly my favourite economic concept, elegantly expressed as Decroissance in French) also suggests we personally and nationally put a scalpel between our wants and needs. Degrowth is, in a sense, an economic diet. We need to reduce out over-sized economies to something that is going to be more sustainable for the planet.

That’s for society, but I’m not sure whether Degrowth articulates the implication that we, personally, also need to rethink our own over-sized lives to bring them into something that is more sustainable for the planet. This is hard to do. If you are the only prophet in the city you tend to look like a bit of a crazy. But if good leaders help us to see that this could in fact be the most practical and necessary approach then it can become a shared, enriching experience, to walk this path together. (Togetherness is an essential need.)

Some sustainability advocates get this needs reduction mandate and challenge us to reconsider our needs through Buy Nothing New Challenges.

To further reduce our assumed needs, what if we also tried:

- Fly nowhere (as Rob Hopkins does)

- Go car-less (as Artist as Family do)

- Eat only local – and only what’s needed

- Earn the bare minimum (As Mark Boyle did)

- Share everything

- Invest X hours/week enriching a meaningful relationship.

- Live small (a la the Tiny House movement)

- Ditch all the streaming services

- Cancel your social media accounts

Essentially, we could test a wants-reduction-diet, across multiple fields where we’ve traditionally expected more or haven’t even thought about how our consumption might have fallen into the overshoot part of the Doughnut (e.g. our internet use is one likely culprit).

Like any good diet we then need to add in the good things. It’s like cutting out what we want (chips) and replacing them with what we need (good fats like coconut oil and avocado).

And Max-Neef’s Needs Matrix can help us. He tells us what those good and essential needs are, the building blocks to a good life. These needs are what the 1987 Brundtland definition of sustainable development relied on – not meeting our current wants by continuing consumption and product innovation. but suggesting we first scrutinise our needs.

According to Max-Neef these needs are:

- Subsistence

- Protection

- Affection

- Understanding

- Participation

- Idleness

- Creation

- Identity

- Freedom

These are expressed through ways of:

- Being

- Having

- Doing

- Interacting

Examples are:

- eating (doing subsistence)

- hugging (doing affection)

- friendships (having affection)

- customs (having identity)

- theatre (interacting creativity)

I’ll offer a controversial example. Some may say, “see I express my need for freedom through doing overseas travel.” This may be the case, but we should be honest with ourselves, overseas travel is a massive privilege that very few people through all of history have been able to access. Did they then live without being able to express the freedom they essentially needed? Not likely. Possibly they were able to express the same need through going on a long walk or swimming in a beautiful waterhole, or in the way they lived – not so attached to work and jobs as we tend to be these days (earning for the overseas travel – see, it’s the ouroboros). No need to pump fossil fuel out of the earth to fulfill that essential need for freedom, we need to find less energy intensive ways to fulfill our essential needs and place our wants firmly in the privilege pile.

If we’re serious about sustainability, we do actually need to make it normal, together, to need less. So that our grandchildren won’t suffer from the fact that we took more than we needed. I for one don’t want to be the one crazy person in the village – I have tried it and it doesn’t seem to be very effective anyway. But I also don’t want a life lived in excess to weigh on my conscience. It would be nice to know we were all living in a way the earth could support – together.

As Margaret Mead famously quipped: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

When we’re courageous enough to say “enough”, that’s when we won’t be swallowed up by an economic system that demands too much.